by Jim Gawel, Ph.D., UW-Tacoma

Wapato Lake is a small, 23-acre lake in the highly urbanized area of south Tacoma, and has attracted visitors since the late 19th century. Wapato has a long history of water quality problems and management activities and has been closed to recreational use four different times over the years due to poor water quality.

A history of water quality problems for an urban lake

Wapato Lake first opened to the public in 1889 and in 1910 Tacoma’s park board recommended that the Metropolitan Park District of Tacoma buy the lake and the surrounding area for recreational use (McGinnis 2005). The purchase was completed in 1920, bringing in more swimmers and visitors as well as continuous park development from 1926 to 1928 (McGinnis 2005). The first closure occurred in 1942 after swimmers reported rashes, thought to result from overland sewage entering the lake (McGinnis 2005). A sewer improvement project was installed in 1945 and the lake was once again open to swimmers in 1948 (McGinnis 2005). Wapato Lake was closed again in 1957, after complaints to the Park Board of an “unpleasant smell.”

By 1966, the park was awarded an Urban Beautification Grant for lake rehabilitation and storm drain improvements. Using these funds, cleanup efforts for Wapato Lake began in 1971 with the mechanical removal of aquatic plants that covered more than 90% of the lake’s bottom. The aquatic plant removal seemed to have little effect on the lake’s continuing algae problems (Entranco 1986). In 1981 a diversion dam and stormwater bypass system were constructed, creating two separate basins. The North Basin now has a surface area of 2.5 acres and a volume of 6.7 acre-ft (there are also about 6.5 acres of wetland), while the larger South Basin has an area of 20.5 acres and a volume of 107.2 acre-ft. The bypass system diverts almost all stormwater around the South Basin via storm drains, allowing only occasional overflows over the weir into the South Basin during significant storm events. In addition, drinking water was injected into the South Basin to dilute phosphorus concentrations. An alum treatment conducted in 1984 had disappointing results (Entranco 1986). The dilution system was discontinued when it was found that the water used was often high in phosphorus.

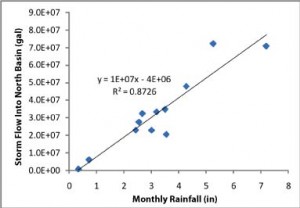

Correlation between monthly rainfall (in) and monthly storm flow (gal) into the North Basin of Wapato Lake during water year 2010.

Because of toxic algae, the lake was once again closed to recreational use in 1997 and was nicknamed “Duck Poop Park” by local citizens. A study completed in 2007 showed that phosphorus levels were double what they had been in 1975 (Tetra Tech 2007). With few aquatic plants and reported deaths of turtles and waterfowl, the study showed that toxic algae blooms were causing serious problems in the lake (Tetra Tech 2007). To reduce concentrations of toxic algal growth, an alum treatment was applied in July of 2008. Incorrect chemical concentrations used during the treatment resulted in a large pH drop and a massive fish kill. Algal blooms reappeared soon after the treatment.

Any long-term solution to the lake’s water quality problems needs to take into account the fact that the primary hydrological inflow into Wapato Lake is urban stormwater runoff, providing a constant source of new nutrients to the lake. Long-term control of algae growth cannot succeed if source control is not addressed.

Recent studies add to understanding of the lake’s hydrology

To quantify more completely the hydrology and nutrient budget of Wapato Lake, an intensive study was conducted from 2008-11 by citizen volunteers and students and staff from the University of Washington-Tacoma, in collaboration with staff from the City of Tacoma’s Environmental Services. The study focused on water year 2010 (October 2009 to September 2010) and assessed nutrient inputs and outputs to Wapato Lake to better inform management decisions and more effectively address nutrient source control in the future.

The construction of a dike and stormwater bypass system separating the North and South Basins of Wapato Lake in the early 1980s effectively created two very different lakes. The water budget for the North Basin of Wapato Lake is dominated by stormwater running off from a large urban area in South Tacoma, with all this water leaving either through the bypass drain or evaporation. During water year 2010, no water entered the South Basin over the weir; all inflows into the South Basin came from direct rainfall on the lake or overland runoff from the surrounding Wapato Park. As the contributing area is quite small relative to the volume of the South Basin, the basin has a long flushing time (~8.5 years) and little movement of nutrients out. Moreover, during the summer, with little rainfall, evaporation in the South Basin concentrates nutrients in the basin’s water column. Groundwater appears to have little influence on the hydrology of the South Basin.

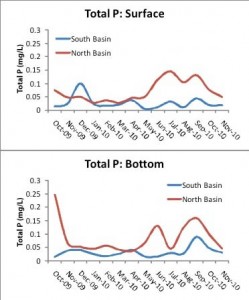

Total P concentrations in surface and bottom waters of the North and South Basins of Wapato Lake during water year 2010.

A large flux of nutrients is associated with the stormwater flow into the North Basin. About half the phosphorus influx leaves via the bypass drain, while the other half is deposited in the North Basin sediments. In the South Basin, nutrients are added primarily via overland park runoff and waterfowl droppings. Sedimentation rates in the South Basin were high, but may have been affected by the alum treatment. Little phosphorus leaves the South Basin, resulting in a net accumulation of phosphorus.

Water column measurements showed distinct correlations between chlorophyll a (from phytoplankton), Secchi depth (a measure of water clarity), and total phosphorus. All values were elevated in the summer of 2010, indicating mesotrophic (medium algae growth) to eutrophic (high algae growth) conditions in the lake. However, chlorophyll a values and Secchi depth collected by volunteers in 2009 and 2011 indicated strongly eutrophic conditions. The short-term improvement seen in 2010 is most likely due to colder, wetter conditions during that water year. High phytoplankton biomass was also recorded in 2010, dominated during much of the summer by the cyanobacteria Anabaena sp. Release of phosphorus in the South Basin is much less than in the North Basin, although bottom water concentrations in the South Basin indicate some sediment release during the summer even after alum.

Other water column data showed that the 2008 alum treatment is still affecting the lake’s South Basin. Specific conductivity and pH both show evidence of continued adjustment throughout the water year as the slow flushing clears the chemicals left from the treatment.

Lake management changes could help Wapato’s water quality

Overall, the 2008-2011 study highlights the need to address ongoing inputs of nutrients to the South Basin from overland park runoff and waterfowl, as these appear to be the primary sources of new nutrients to this basin. In addition, it may be necessary to control phosphorus release from the sediments using a regularly operating treatment system in conjunction with aquatic weed control to prevent the pumping of nutrients out of the sediment via plant uptake.

Secchi depth (m) recorded from 2008-2011 in the South Basin of Wapato Lake by UWT staff and volunteers.

Water quality would also be improved if the North Basin were actively maintained to maximize nutrient removal from stormwater, and if treated stormwater were used to decrease the flushing time for the South Basin. Although there was no overflow of the weir during the 2010 water year, overflow events occurred in water years 2008 and 2009 when rainfall surpassed one inch in 24 hours. To prevent large additions of nutrients to the South Basin during these events, sediment retention should be increased during high flow events, possibly through increased sinuosity. High flow events could also be a way to feed stormwater to a treatment system and add treated water to the South Basin.