By Edward J. Johannes, Deixis Consultants, SeaTac, Washington

Washington State likely has nearly 8,000 natural lakes. The majority of them were created during the last glacial period between 10,000 to 20,000 years ago, which is why the bulk occur in the northern half of our state. For most government agencies, lake management has mainly focused on them as sources of water, for sport fishing, boating, and as public swimming facilities. Other than game fishes, the preservation of lake biota has not fully entered the governmental mindset, except peripherally. Despite the importance of mollusks in the ecosystem and their susceptibility to habitat loss, they are invariably overlooked during macroinvertebrate surveys of lakes or other aquatic systems or in lake management. In addition, only piecemeal biological surveys of Washington lakes have been done for mollusks.

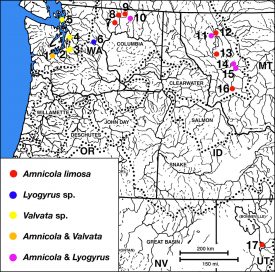

Figure 1. Lakes where Washington valvata (Valvata sp.), mud amnicola (Amnicola limosa) and masked duskysnail (Lyogyrus sp.) are found (see full explanation at bottom of article**)

Since the mollusk fauna of Washington lakes is very poorly known, it should come as no surprise that two glacial relict snails, mud amnicola (Amnicola limosa) and Washington valvata (Valvata sp.; possibly a new species), were found in Pattison Lake during a 2010 survey of all water bodies within a five-mile radius of Olympia’s Capitol Lake for the introduced New Zealand mudsnail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum). Far from being off the beaten path, this easily accessible lake is in a region that has been long settled and surveyed for mollusks.

Malacologists in the 1940s and 50s discovered both snails — the Valvata in Paradise Lake, northern King County and the Amnicola in the McWinnegar Slough, Flathead River drainage in northwestern Montana. The mud amnicola was also found earlier in the 1800s in Utah Lake and is now extinct there. Amnicola limosa was discovered in northeastern Washington lakes in the early 1990s during surveys for another glacial relict snail, the masked duskysnail (Lyogyrus sp.; taxonomic status uncertain pending further study of the species of this genus). This snail was originally found in Fish Lake, Wenatchee River drainage, Chelan County during a mollusk survey conducted for the precursor to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in the late 1970s. Of the three glacial relict snails, Lyogyrus sp., is the only one with some federal protection; it was designated a Clinton Forest Plan ROD (Record of Decision) species in 1994. Surveys conducted in 2000s in Montana have uncovered additional sites for Lyogyrus and Amnicola. In 2014, Amnicola limosa was found in Leader Lake, Okanogan County by Ernie Buchanan, an avid fisherman, when he investigated the stomach contents of a brown trout he caught. Additional sites were found for the Valvata sp. in 2012 and 2014 using the glacial history of the Puget Sound region and lake preference criteria of the species. No sites or museum records for the Valvata sp. or Lyogyrus sp. have been found in British Columbia, but there is one unverified record for Amnicola limosa occurring as fossils in a lake deposit in the Fraser River drainage.

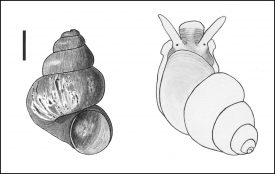

Figure 4. Apertural view of shell (left) and live animal (right) of Amnicola limosa from Pattison Lake, Thurston Co. Measurement line= 1 mm.

All known sites for Valvata sp. and most for Lyogyrus sp. and Amnicola limosa occur in glaciated terrain north of the terminus of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet and mostly in kettle lakes, which must have stream outlets. Both the Lyogyrus sp. and Amnicola limosa are snails with ranges found almost entirely east of the Continental Divide. For both, the Washington occurrences are the furthest west these genera are found. It is likely these two glacial relicts, with a handful of other eastern U.S. snail species, crossed the continental divide during the last glacial period into northwestern Montana from the upper Missouri River drainage. This is supported by the occurrence of four western U.S. mollusk species in the upper portion of that eastern drainage (one being a unionid clam, the western pearlshell (Margaritifera falcate)).

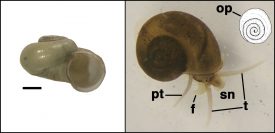

Figure 5. Apertural view of shell from Paradise Lake, King Co. (left) and live animal from Pattison Lake, Thurston Co. (right) of Valvata sp. f, foot; op, drawing of multispiral operculum; pt, pallial tentacle; sn, snout; t, tentacles. Measurement line= 1 mm.

These glacial relict snails require a well-oxygenated environment and have not been found in lakes that are strongly eutrophic or have anoxic substrates. The snails appear to inhabit only lakes with soft substrate and aquatic macrophyte beds, with streams entering and especially exiting. Lakes with glacial relict species generally have a higher molluscan diversity than adjacent lakes without these species. They are also sensitive to pollution or siltation caused by grazing or human development or activity. These snails are not found in lakes that have been heavily treated with rotenone to kill native fish or those that have had extensive herbicide treatment (especially copper-based).

Figure 6. Apertural view of shell (left) and live animal (right) of Lyogyrus sp. from Curlew Lake, Ferry Co. Measurement line= 1 mm.

Globally, freshwater mollusks have suffered the highest number of documented extinctions of any major taxonomic group. In North America, they suffer much higher rates of imperilment than most terrestrial groups, including birds and mammals. Currently there are no conservation strategies or management procedures for mollusks in Washington lakes. The native molluscan fauna of lakes is imperiled by human activity, especially now in the Puget Sound basin, which has experienced rapid growth over the last several decades – a trend likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Climate change will impact the common mollusks, but especially the cold-water mollusks such as the glacial relict snails, which need lakes that maintain a thermocline throughout the summer months to survive.

Mollusks can serve as important indicators of the health of lentic ecosystems. Snails are especially sensitive to acidification of lakes and will disappear before the fish do, reducing fish production. The native lake mollusk fauna is also endangered by possible introductions of the New Zealand mudsnail, which has recently invaded additional drainages in the south and central Puget Sound region.

With the exception of few ancient lakes, most lakes – especially kettle lakes – exist for a short time geologically. One would think these species would be short lived as well, but it is likely they survived through several cycles of glaciation, which probably formed and destroyed kettle lakes over and over. It is up to us to preserve these snails’ habitat so they can go on quietly living until the end of this interglacial period and into the beginning of the next glacial cycle, which will undoubtedly form new kettle lakes for them to reoccupy.

Figure explanation:

**Figure 1. Lakes where Washington valvata (Valvata sp.), mud amnicola (Amnicola limosa) and masked duskysnail (Lyogyrus sp.) are found in Washington, Montana and Utah. Washington: 1-Pattison Lake, Thurston Co.; 2-Ravensdale Lake, King Co.; 3-Walsh Lake, King Co., 4-Paradise Lake, King Co.; 5-Lake Campbell, Skagit Co.; 6-Fish Lake, Chelan Co.; 7-Leader Lake, Okanogan Co.; 8- Spectacle Lake, Okanogan Co.; 9-Bonaparte Lake, Okanogan Co.; 10-Curlew Lake, Ferry Co.; Montana: 11-Smith Lake, Flathead Co.; 12-McWenneger Slough, Flathead Co.; 13-Ninepipe Reservoir, Lake Co.; 14-Upsata Lake, Powell Co.; 15-Browns Lake, Powell Co.; 16-Georgetown Lake, Granite and Deer Lodge cos.; Utah: 17-Lake Utah, Utah Co. (likely extinct). Data on Montana sites not visited by Deixis (11, 14, 15 & 16) are from Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History online collection database.