by Callie Mathieu, Natural Resource Scientist, Washington State Department of Ecology, and Katelyn Foster, Natural Resource Scientist, Washington State Department of Ecology

Eating locally caught freshwater fish can be a significant source of human exposure to a group of harmful chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Because some PFAS are bioaccumulative, they can build up in aquatic food webs to levels that are a concern for human health and wildlife. Ecology has tested PFAS in freshwater fish over the course of several studies since 2008, documenting widespread occurrence of PFAS across the state and highlighting the need for more comprehensive testing. To fill that data gap, we carried out a 2023 study on PFAS in ten lakes to better understand PFAS concentrations across a range of waterbodies and fish species.

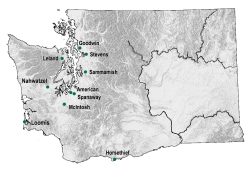

In the fall of 2023, we collected 324 fish from ten lakes in Washington: American, Goodwin, Horsethief, Leland, Loomis, McIntosh, Nahwatzel, Sammamish, Spanaway, and Stevens. Fillet tissues were analyzed for PFAS as 75 composites and 13 individual samples. Three surface water samples were also collected from each lake for PFAS analysis.

PFAS were detected in almost all fish tissue samples (83 out of 88). Total (T-) PFAS concentrations were highest in American Lake fish, ranging from 8.4 – 204 ng/g (nanograms per gram, parts per billion), followed by Spanaway (24 – 99 ng/g) and Stevens (6.2 – 99 ng/g), all of which had median and means above 10 ng/g across all species collected. The remaining lakes were generally from less-developed watersheds and contained much lower PFAS concentrations. Of these, Goodwin had slightly elevated concentrations (T-PFAS above 10 ng/g) in bass samples, and several samples from Leland Lake had higher concentrations of the precursor compound (N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamidoethanol, or NEtFOSE). All other fish samples from the more rural lakes and cutthroat trout samples from Lake Sammamish contained T-PFAS concentrations of less than 5 ng/g.

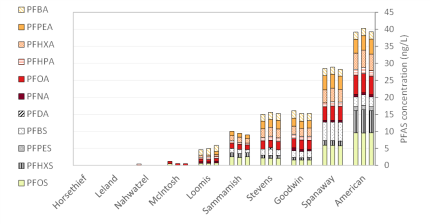

Surface water samples from all lakes but Leland and Horsethief contained detectable levels of at least one PFAS. The highest T-PFAS concentrations were found in American Lake at 39.6 ng/L (nanograms per liter, parts per trillion), followed by Spanaway (28.6 ng/L). Stevens and Goodwin – both of which are surrounded by a mix of urban, suburban, and forested land – contained average T-PFAS concentrations of 15 ng/L. The rest of the lakes had average surface water T-PFAS concentrations of less than 10 ng/L: Sammamish (9.5 ng/L), Loomis (5.2 ng/L), McIntosh (0.7 ng/L), and Nahwatzel (0.4 ng/L). We found a correlation between fish PFAS concentrations (bass and sunfish) and surface water PFAS concentrations, with fillet levels increasing as surface water levels increased, suggesting that preliminary screening of surface water could help prioritize water bodies for future fish collections.

PFAS concentrations in the 2023 fish and surface water samples were well below state aquatic life criteria, which were based on draft US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommendations for observed effects on the survival, growth, and reproduction of aquatic organisms (USEPA 2022). However, when compared to the more stringent final EPA aquatic life criteria recommendations (USEPA 2024), several fish samples from American Lake and one from Spanaway Lake exceeded limits for perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), indicating potential risks to aquatic life in those lakes (USEPA 2024). PFOS is a compound within the PFAS class of chemicals that is highly persistent and bioaccumulative and typically makes up the the majority of detected PFAS in fish tissue.

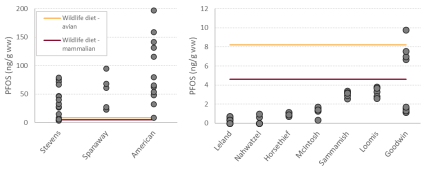

The aquatic life criteria described above are protective of direct harm to fish themselves, but do not address risks to wildlife that eat the fish, like birds or mammals. While the US does not currently have surface water or fish tissue PFAS thresholds that are protective of fish-eating wildlife, Canada has issued wildlife dietary guidelines for PFOS (whole body fish tissue): 4.6 ng/g for mammals and 8.2 ng/g for birds (ECCC 2018). Figure 4 compares samples collected for this study to the Canadian wildlife guidelines. PFOS levels in American, Spanaway, Stevens, and some Goodwin fish were high enough to be harmful to wildlife consuming the fish. The other lakes sampled were below levels of expected ecological impacts.

Figure 4. Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) concentrations in the 2023 freshwater fish species fillet samples compared to wildlife consumer guidelines. Yellow line = Environment and Climate Change Canada’s whole body fish tissue federal guideline for avian wildlife diet; red line = Environment and Climate Change Canada’s whole body fish tissue federal guideline for mammalian wildlife diet.

Across this 2023 study and previous studies, Ecology has found that freshwater fish PFAS concentrations are highest in lakes within very urbanized watersheds, near military bases, or impacted by wastewater treatment plant effluent. Rural waterbodies tend to have lower PFAS concentrations, but most still have detectable contamination. Our next steps for testing PFAS in freshwater fish will be to integrate PFAS monitoring into our existing statewide fish tissue monitoring program for mercury. Between 2025-2029, Ecology will sample PFAS in edible freshwater fish fillets, with a focus on largemouth and smallmouth bass, and surface water collected from 35 waterbodies. We plan to sample 7 of the 35 sites each year and repeat sampling from the sites every five years to track trends in environmental PFAS levels. Data from this program will also be used for fish consumption advisories and the state’s Water Quality Assessment. Results can be accessed from Ecology’s EIM database and our StoryMap. A published report will summarize the 2025-2029 sampling period after the last year of sampling.

For more information on how the state is addressing PFAS, visit the Ecology website at https://ecology.wa.gov/waste-toxics/reducing-toxic-chemicals/addressing-priority-toxic-chemicals/pfas.

References

ECCC [Environment and Climate Change Canada]. 2018. Federal Environmental Quality Guidelines, Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS).

USEPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency]. 2022. Fact Sheet: Draft 2022 Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (PFOS). EPA 842-D-22-005. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-04/pfoa-pfos-draft-factsheet-2022.pdf

USEPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency]. 2024a. Final Freshwater Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria and Acute Saltwater Benchmark for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS). EPA 842-R-24-003. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water.

USEPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency]. 2024b. Final Freshwater Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria and Acute Saltwater Benchmark for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). EPA 842-R-24-002. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water.