by Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Aquatic Invasive Species Division

Invasive freshwater quagga and zebra mussels (QZM), aquatic invasive species (AIS), pose an imminent threat to Washington’s environment, economy, health, and way of life. While not currently known to be established in Washington, invasive mussels have been intercepted on watercraft at the state border and attached to imported aquarium moss balls. Recent detections of quagga mussels (QM) in the Snake River in south-central Idaho demonstrate the significant risk that invasive mussels could be introduced into Washinton’s waters. Fortunately, protecting our lakes from invasive mussels is possible with your help.

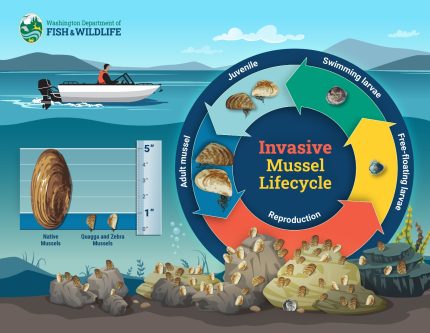

Nearly impossible to eradicate once established, QZM can drastically alter native habitats and threaten fish and wildlife species. Unlike native freshwater mussels, invasive mussels have byssal threads, thread-like ropes that allow them to attach to surfaces like aquatic infrastructure, rocks, aquatic vegetation, and even native species of mussels. A single invasive mussel can produce over one million eggs per year, and, free from predators found in their native Caspian Sea, QZM can reproduce quickly with their microscopic, free-floating larvae using water currents to spread to connected, un-infested waterbodies.

Environmental threats

Environmental threats

QZM alter habitats critical for native species survival leading to habitat loss and broader impacts statewide. Invasive mussels can outcompete natives by attaching themselves to any available surfaces and filtering suspended particles and phytoplankton. This increases water clarity, which might appear beneficial, but it allows sunlight to reach deeper into waterbodies, warming water. These changes disrupt habitat for species and can alter food webs, ultimately harming the lake ecosystem. They also increase avian botulism, causing bacteria, cyanobacteria, and algal blooms which threaten human health. Habitat loss is likely to lead to decreased populations of fish like Chinook salmon, reducing available food for endangered Southern resident killer whales.

Economic impacts

Decreasing populations of fish also impact recreation – a significant concern to Washington’s economy, with more than a quarter of outdoor recreation taking place on Washington’s public waters, generating $5 billion annually. Recreational fishing activities generate more than $1.5 billion in annual economic activity. Additionally, commercial domestic fisheries create nearly 23,000 jobs in Washington and salmon harvest is worth nearly $14 million annually.

Economic impacts aren’t limited to fisheries. QZM have sharp shells capable of injuring people and wildlife. Infestations on shorelines, beaches, and in aquatic recreation areas can change, limit, or even eliminate recreation opportunities. Changes to tourism and recreation opportunities could have serious impacts on the economy and the availability of jobs in communities that depend on them.

Due to their unique ability to attach to surfaces with their byssal threads, quagga and zebra mussels can damage critical infrastructure including water intake pipes, utilities, navigational locks, and dams, putting billions of dollars in industry and trade at risk. If they are introduced to Washington, costs to manage and mitigate QZM infestation could exceed $100 million each year.

Three-quarters of Washington’s agriculture is irrigated, relying on a variety of water sources. While groundwater withdrawals supply irrigation water to many areas, most water used for irrigated agriculture is diverted from streams and rivers, relying on water intake pipes and infrastructure that are at risk of becoming clogged by quagga and zebra mussels. Irrigated agriculture is an industry worth $9.6 billion to Washington’s economy. Disruptions to irrigated agriculture could increase food production costs, meaning higher prices and greater food insecurity statewide. Clogged water intake pipes will also affect the cost and availability of drinking water and changes to critical habitats will require additional restoration efforts.

In 2022, the Columbia Snake River System, a key US trade gateway, handled $31.2 billion in national and global trade. Since it is the leading wheat export gateway in the US and the second export gateway in the US for soy and corn, costs to manage and mitigate the impacts of quagga and zebra mussels along Columbia River Basin trade routes may also contribute to higher food prices and food insecurity.

Prevention is possible

QZM larvae can spread via connected waterways; humans are a major source of transportation between waterways. Contaminated water can transport larvae while adult invasive mussels can attach to aquatic equipment, gear, and watercraft (motorized and non-motorized). Able to survive out of the water for 30 days depending on moisture and temperature, and up to 7 days in freezing temperatures, QZM can travel long distances on infested equipment to unconnected waters.

Overland transportation is preventable. If it’s been in the water, it could be contaminated by QZM or other AIS. Practicing “Clean, Drain, Dry” on all gear, equipment, and watercraft (motorized and non-motorized) is key to preventing accidental transportation of AIS. It also ensures you won’t receive fines up to $5,000 or a year in jail for transporting AIS in Washington.

Clean: Whenever possible, all gear, equipment, and watercraft used on or in the water should be cleaned before leaving the boat launch or water access area. This ensures that potential hitchhikers are left behind.

Drain: Remove all drain plugs and dump all accumulated water.

Dry: Open and air or towel dry compartments on watercraft or gear and let everything fully dry before using it/launching at a new waterbody.

In addition to practicing Clean, Drain, Dry, stopping at free mandatory watercraft inspection and decontamination stations is key to protecting our waters. Inspections are performed on all watercraft and, if they are contaminated or at high risk for transporting QZM or other AIS, free decontamination is provided. Watercraft last used in waterbodies known to be contaminated with QZM, or watercraft that inspectors can see have not been cleaned, drained, and dried are at high risk of transporting QZM and other AIS. At some stations, an AIS detection dog helps with inspections. Mussel detection dogs are trained to identify only the presence of quagga and zebra mussels which can be hard to see.

Help protect our lakes

Keeping our waters free of invasive mussels and AIS is a collective effort — public outreach and awareness are crucial for successful prevention. WDFW is investing in a Protect Our Waters outreach and awareness campaign, but locally led outreach efforts often prove the most effective – fostering strong community ties, good stewardship values, and a sense of belonging. Organizations like WALPA have a unique opportunity to make a difference in protecting our lakes and waters – and WDFW is here to help.

Keeping our waters free of invasive mussels and AIS is a collective effort — public outreach and awareness are crucial for successful prevention. WDFW is investing in a Protect Our Waters outreach and awareness campaign, but locally led outreach efforts often prove the most effective – fostering strong community ties, good stewardship values, and a sense of belonging. Organizations like WALPA have a unique opportunity to make a difference in protecting our lakes and waters – and WDFW is here to help.

If unchecked, invasive mussels will lead to catastrophic consequences for Washington. While WDFW works to intercept invasive mussels at the state’s borders, it’s crucial that anyone who works or recreates on the water remembers to clean, drain, and dry all gear and equipment after every use — especially if you’re headed to another waterbody. Together we can protect our lakes and waters from QZM and AIS.

To learn more about protecting our waters from QZM and AIS, visit the WDFW Prevention Website, call WDFW’s Aquatic Invasive Species hotline at 1-888-WDFW-AIS, or email ais@dfw.wa.gov.